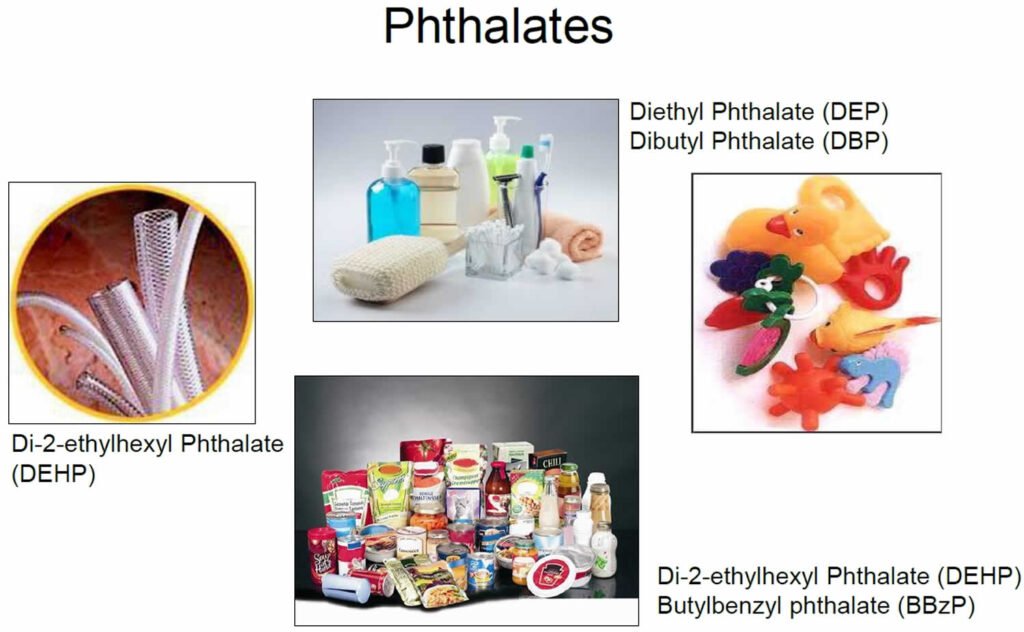

Scientists are only now beginning to understand how phthalates—chemicals prevalent in hundreds of ordinary home products and cosmetics—are connected to these frequent tumors in women.

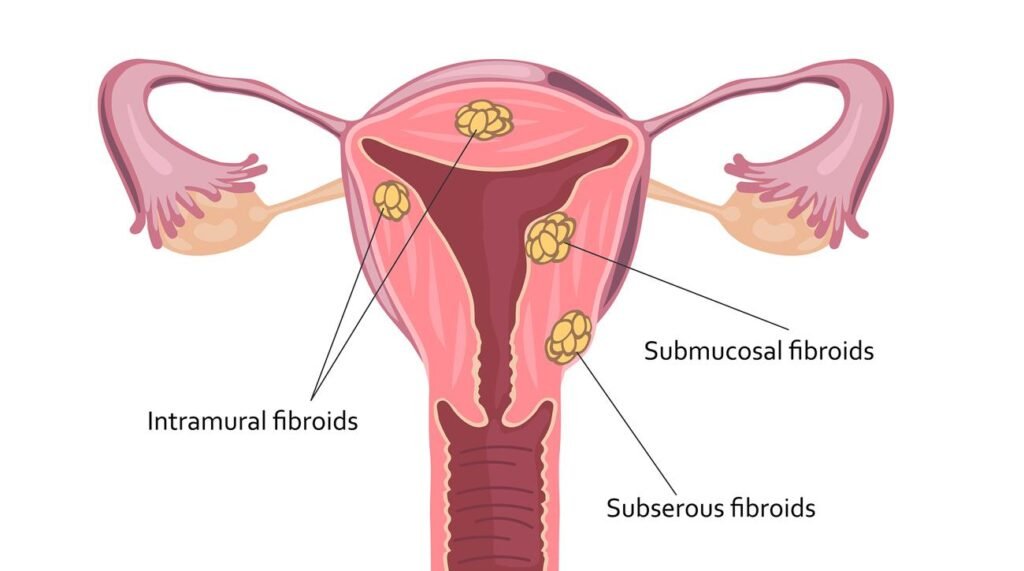

Pthalates, which are present in hundreds of household items, have been related to uterine fibroids, which are non-cancerous tumors that range in size from a seed to a soccer ball and develop in or around the uterus. Millions of women are affected by fibroids, which can cause pelvic and back discomfort, excessive monthly flow, pain during sex, and reproductive issues.

Ami Zota, an environmental health expert now at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, discovered in a preliminary study published in 2019 that greater levels of phthalates in urine, particularly metabolites of DEHP —a chemical that’s commonly added to plastics to make them flexible— were related with bigger fibroids and an enlarged uterus in Black women in the United States undergoing surgery for fibroids.

This Phthalates research reinforces the link between these ubiquitous chemicals and a disease that’s greatly underappreciated

These “everywhere chemicals,” can leach out of products namely food packaging and processing equipment, shower curtains, building materials, PVC, car interior etc. and enter food, air, and water, meaning people can swallow, inhale, or absorb these phthalate particles through direct skin contact. The body then metabolizes these chemicals, yielding byproducts that several studies have detected in human urine, breastmilk, and blood.

A November 2022 study, demonstrated the molecular mechanism behind how a major DEHP byproduct called mono-(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate affects tumor cells. The team found that the chemical helps tumor cells absorb an amino acid called tryptophan that gets converted to a compound called kynurenine which activates a protein receptor called AHR (aryl hydrocarbon receptor) that is known to initiate cancer. This active receptor promotes the growth of fibroid cells leading to larger growths.

However, establishing causality is difficult. Phthalates take hours to break down in human bodies, and amounts can change by many orders of magnitude on a daily basis. Knowing the exposure levels at the time the disease begins is also vital, but it is nearly hard to determine in the actual world.

“We cannot alter our age, gender, or heredity, but we can minimize the quantity of chemicals we consume. This way we still will have a firm grip on the situation.”

Reference- National Geographic story, National Library Of Medicine, ACS Publication story, PNAS Article