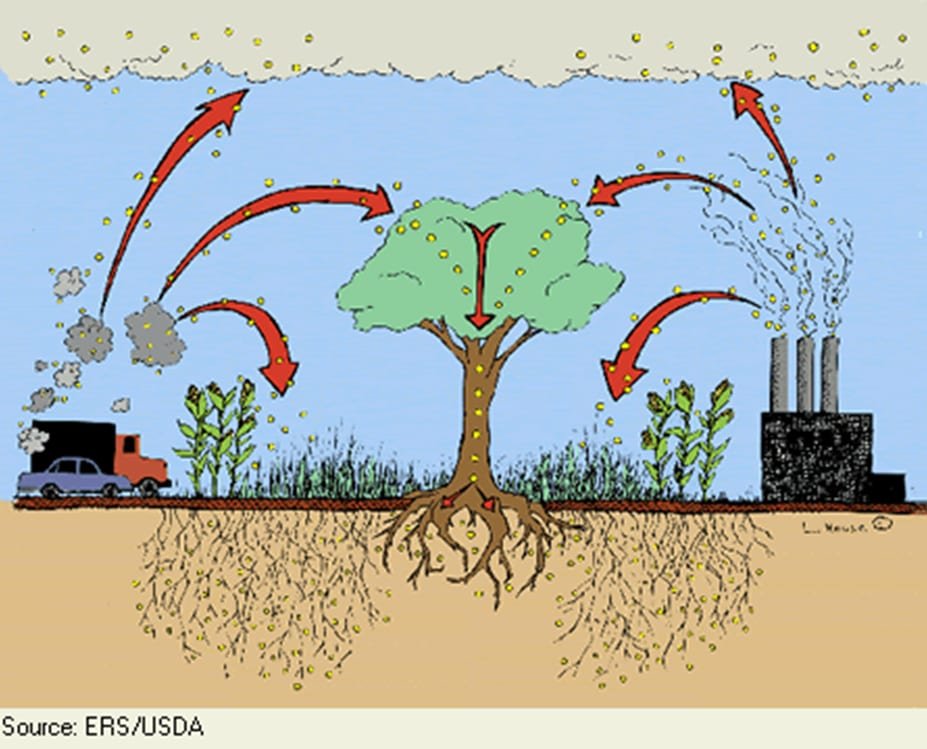

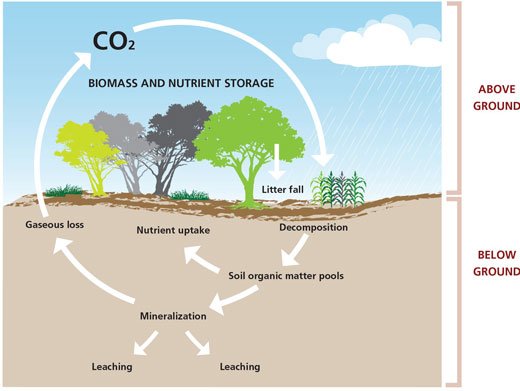

Increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) is now visible in plants such as wheat, maize, rice, and other crops, meaning that they do not accumulate as much nitrogen, phosphorous, and other nutrients, according to a Harvard University demonstration in 2014 by planetary health scientist Samuel Meyers.

The idea from this is that roots cannot keep up with the growth stimulated by the extra carbon and simply don’t provide the right amounts of the other elements.

Most of the concern has been focused on human health since that revelation — if we are eating plants that normally have a certain amount of nutrients but are no longer getting those nutrients due to excess CO2 levels, then we are pretty much eating empty calories.

Ellen Welti, a postdoc student of ecologist Micahel Kaspari at the University of Oklahoma, did more research on 30 elements in samples of various grass species collected and stored by the Kansas LTER every year.

Her research determined that the biomass of the grasses doubled over the past 30 years while the plants’ nitrogen content declined about 42%. Other elements that showed decline were phosphorous by 58%, potassium by 54%, and sodium by 90%.

Imagine — if we aren’t getting the needed nutrients, how does this affect insects that also rely on these plants for nutrition?

Many studies have been documenting dwindling insect populations to the point that the phrase “insect apocalypse” has been coined.

Reference- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Clean Technica, Nature