More than 100 green nets may be found on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, during the gloomy, overcast months of fall and winter, collecting a surprise resource—fog.

In its simplicity, the technique is beautiful. Water vapor condenses into liquid water as it caught in vertical nets and drops into a holding tank. The device, which consists of only two poles and a nylon net, may be a considerable supply of water, gathering between 50 and 100 gallons each day from the fog.

It is the sole means for others to obtain this crucial resource.

Lima, which is blanketed in coastal mist for half of the year, is the world’s second biggest desert city. Furthermore, migrants residing on the fringes of the city lack access to plumbing that provides safe drinking water. The water collected from fog nets isn’t potable, but it can be used for bathing or boiled for cooking, cutting down on how much water needs to be purchased.

According to the United Nations, around two-thirds of the world’s population faces water shortages at least once a year, and by 2030, 700 million people may be compelled to relocate to obtain water.

The basic success of fog nets gives optimism that low-cost technologies might assist people in surviving climatic change.

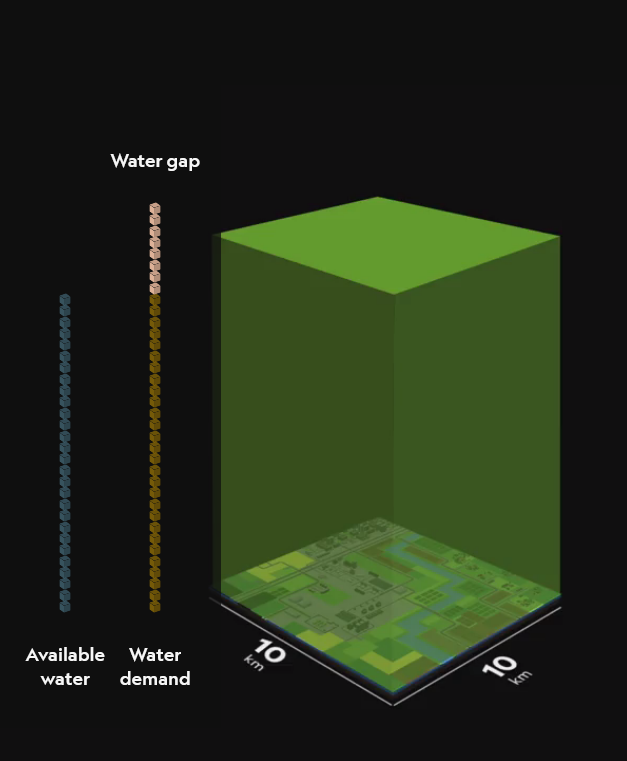

A new World Water Map allows people to find out about the water supply where they live. Typing in an address will reveal that area’s water gap—the difference between human demand for water and the renewable supply from sources such as rivers, lakes, and aquifers.

The map also shows the regions where the water gap is highest and groundwater depletion most dire, including California’s Central Valley, Egypt’s Nile River Delta, and Pakistan’s Indus River Basin.

Reference- National Geographic , UN Report, Discovery Magazine, BBC Earth